Abi Hackett and Ruth Levene

In our planning for our ‘feeding’ workshop, we saw three themes running through the question ‘what is toddler through feeding?’

- Time

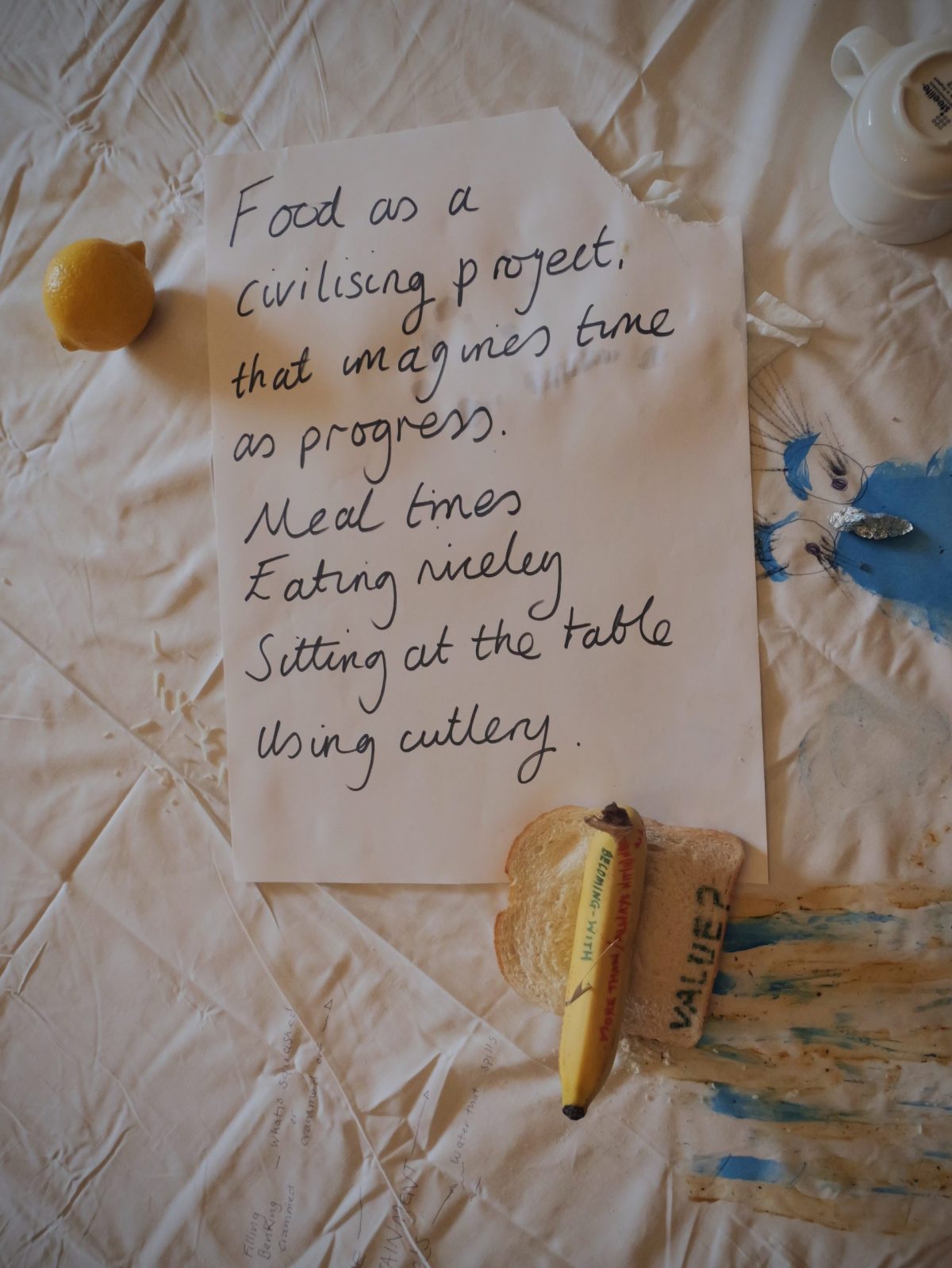

Time, as we have noted through this project, is bound up with notions of progress and the linearly developing child. Within this, feeding can often be viewed as a ‘civilising’ project – where the young child must be shaped to behave in a more ‘civilised’ way as time passes, by being encultured to ‘eat nicely’ (Albon and Hellman, 2019; Nxumalo et al, 2011). Practices such as partitioning food time off from other times of the day (like playtime) and coupling it with specific bodily practices like sitting at the table and using cutlery – have a long and messy colonial history of being presented as natural or superior modes of feeding.

Food is bound up with the idea of the civilising project that imagines time as progress.

Meal times.

Eating Nicely.

Sitting at the table.

Using Cutlery.

- Containment

Humans in general, and the child in particular, are often assumed to be contained and separate, with clear and impermeable boundaries. For example, the child’s body and brain are (both) imagined as (separate) containers, and the focus is enduringly on the child as an individual – and evaluating what we find inside this container. How do we measure or assess its content? From this perspective, the development of the individual child belongs only to them.

We have explored through this project the myriad ways this logic seems to fall apart. Feeding is a particularly striking example of a process of human exchange and growth with the more-than-human world. This exchange and growing-with is the foundation of all living organism’s development (respiration, metabolising, composting). As Tim Ingold writes “things can exist and persist only because they leak” (Ingold, 2013, p.95). And yet, our imaginaries of humans are exceptional and distinct from the rest of the living world seem to rely on understanding the process of feeding children as distinct and different from this.

Food becomes us and we become food.

Yet we tell stories about separateness.

The individual developing child, capable of being separated from their world and measured.

- Buckets

We also considered how feeding comes to be used metaphorically, to inform a broader policy rhetorics about toddler development. In this narrative, the child is viewed as a bucket to be filled – and their development as additive rather than as a process of change. We see this, for example, in government campaigns such as Hungry Little Minds, in which words are imagined as nutrition, to be fed into the child in order to sustain progress towards desired outcomes such as school readiness. The recent NHS campaign, Load Them Up, similarly proposes life with toddlers as a process of adding and accumulating necessary ‘stuff’ (be that words or five a day vegetables).

Toddlers as empty buckets to be filled.

But what is squashed or spills out, particularly if we cram things in too quickly?

References

Albon, D. and Hellman, A. (2019) Of routine consideration: ‘civilising’ children’s bodies via food events in Swedish and English early childhood settings. Ethnography and education, (14), 2, 153.169.

Ingold, T. (2013) Making. Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge.

Nxumalo, F. Pacini-Ketchabaw, V. and Rowan, M. C. (2011) Lunch Time at the Child Care Centre: Neoliberal Assemblages in Early Childhood Education. Journal of Pedagogy 2 (2), 195-223.