Vik de Rijke

(images have been changed to ensure all have commons permission to post).

The adult market is flooded with literature such as Getting the Blighters to Eat, Healthy Eating for Toddlers, Just One Bite, etc. The expectation is that toddlers won’t want to eat healthily, have limited palettes and are picky eaters, fuelling parental anxiety about failing to feed, eating disorders and so on. This has prompted a large body of smug parental, educational or child bragging literature about “developing children’s palates”. In fact, toddlers’ digestive systems only gradually develop the ability to digest foods and gut motility varies enormously. Also, food is never (necessarily) just food, especially in literature. Neither is swallowing or being swallowed. They are all metaphors – or ‘matterphors’ (Cohen and Duckert, 20151) of gastronomic proportion.

Children’s literature shows us a range of powerful myths and metaphors about eating and being eaten. We might shrink to bite size, trolls and crocodiles lie in wait for us, or, like Jonah or Pinocchio, we might be swallowed by the whale. Feminist critic Marina Warner calls Cannibal Tales ‘The Hunger for Conquest’. This view chimes with Rituparna Das’s2 postcolonial reading of cannibalistic tales from Bengal, emphasising the narrative trope of races, cultures and marginalised ‘others’ being traumatised and ‘devoured’ by white colonialism in its search for political domination. Are toddlers likewise swallowed by adult culture?

Yet, in The Wolf, the Duck and the Mouse written by Mac Barnett and illustrated by Jon Klassen (2017), when a mouse is swallowed by a wolf, he discovers a duck already living inside his belly and living rather well. Do you miss the outside?” “I do not!” said the duck. “When I was outside, I was afraid every day wolves would swallow me up. In here, that’s no worry.” Duck has assimilated being swallowed, not as separation, isolation or marginalisation, but as integration. “I live well” he says, “I may have been swallowed, but I have no intention of being eaten”. He and the mouse feast and party in the belly, while the wolf gets tummy-ache.

Children’s literature reflects our darkest fears about having no food or becoming food. A great famine struck Europe in 1314, where folklore has it that mothers abandoned their children, and, in some cases ate them. The brothers Grimm, researching fairy tales, discovered villages with cemeteries full of gravestones of young women who had died early, indicating mothers had in fact starved themselves so their children and husbands could eat. Versions of Hansel & Gretel already existed, like the C17th Italian Nennilo & Nennela, where a cruel stepmother forces her husband to abandon his 2 children in the forest, or a Romanian version where the wicked stepmother kills the little boy and forces his sister to cook him for the family meal. Tales such as these carry lasting food tropes that bother us to this day: times of plenty and want, the longed-for sugar of the gingerbread house, the evil female mother-figure, thinness as Hansel is tested to see if he is fat enough to eat yet, and ultimate solution ovens like the one Gretel pushes the witch into.

From the 20th century, children’s books became more likely to depict an excess of food. Richard Scarry and Eric Carle’s books such as The Very Hungry Caterpillar (1969) picture great plenty, focusing strongly on mealtime excess, perhaps as both authors lived through the Depression into the mass marketisation of American capitalism. Pulling up the Turnip is a cumulative Russian folk tale, also well known in the Ukraine and found echoes in tales like Chicken Licken across Europe. As grandfather, grandmother, grandchildren, pets and finally a mouse pull up the enormous turnip, the importance of collective effort, where work and resources are controlled and shared by community throws up alternatives to capitalism. In the early stages of multicultural education, food became a key element of diversifying school curricula, as a means of teaching and learning about difference in non-threatening ways. Critics of affirmative action argue it does not address race inequity but smooths harmful stereotyping and discrimination out for cheerful, colourful but imaginary interracial harmony and inclusivity.

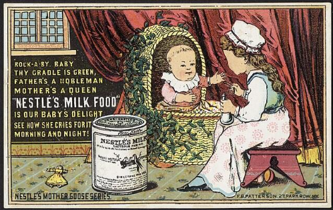

And now to milk. Depicted in the arts as the first food, milk is associated with stories of creation, divinity, and of course motherhood. Milk as the magic of Isis, Yashoda with the infant Krishna or Lakshmi emerging from the churning of the milky ocean. In Islam and many African and indigenous cultures, breastfeeding has always been a vital traditional practice, grossly disrupted by colonization, yet venerated in the arts from Da Vinci to Mary Cassat, with all that cultural baggage appearing in children’s literature, too.

The dark sides to milk include the giant corporation Nestlé’s aggressive marketing of breast milk substitutes that led to infant deaths and health crises in developing countries, prompting a major international boycott against the company from 1977. This scandal linked human rights regulations and humanitarian activism with corporate responsibility, emphasising the unethical results of global colonial capital practices. It has not stopped: in 2024, a report by nonprofit researchers stated that Nestlé adds more sugar to baby food sold in lower- and middle-income countries compared to healthier versions sold in richer markets. The majority of the world (Global South) is lactose intolerant, 70% of people losing the enzymes to digest lactose after infancy, whereas cultures with histories of animal domestication and milk consumption (like Europeans and Americans) are more typically lactose persistent. Far right, fascist and neo-Nazi groups from Brazil’s Bolsonaro to America’s Maga groups for Trump have reframed this, staging public milk drinking as acts of white male supremacy.

Milk is therefore a metaphor: for gender, making little girls sweeter and making men of little boys. It has been marketed as a patriotic victory food, linked to IQ or intelligence, and most of all, to children’s development into tall, able-bodied, normative individuals.

But the best children’s literature is much less black and white about things. Maurice Sendak’s picturebook In The Night Kitchen of 1970 was controversial from the start: for his flat, comic-book illustrations, for its fantasy about a toddler Mickey waking up in the night and flying over the milky way into the night kitchen. As a Jewish New Yorker, Sendak has spoken of thinking about the landscape of the city as food, the ovens of the Holocaust and the infant’s desires to be allowed to do what adults do at night. The book marked the first depiction of full-frontal nudity of a male child in a book for young readers.The book’s reception was hostile (often censored for nudity, drawn over or holes cut out; frequently banned reading for children and was on the “100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–2000” in the US). As an artist, Sendak was of course horrified. The book has had many Freudian interpretations as a ‘masturbatory fantasy’ or celebration of ‘infantile polymorphous sexuality’ as Mickey finds himself in the sensual pleasures of dough, diving into milk, getting baked in cake batter and born out of the oven (singing “I’m in the milk and the milk’s in me! God bless milk and God bless me!). Though the multisensory pleasures are many, the adult cooks have mistaken the child for milk. “But right in the middle of the steaming and the making and the smelling and the baking, Mickey poked through and said: I’m not the milk and the milk’s not me. I’m Mickey!” The book finishes with Mickey’s birth out of the batter and his joyful realisation that he is not the milk but himself, back in bed, “cakefree and dried HUM YUM”.

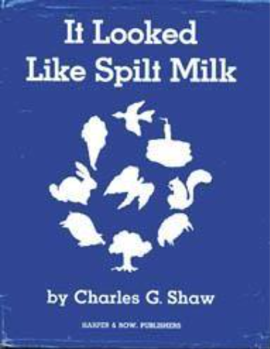

Today, though food books remain plenty, you have to search to find unusual perspectives. Microbiologist Idan Ben-Barak and illustrator Julian Frost zoom in on the microscopic world found on everyday objects—and in our bodies—warning readers Do Not Lick This Book in this interactive picturebook of 2017. Min is a microbe. Simple, funny, and an important acknowledgment of the role of bacteria like E Coli, Salmonella or Listeria – not least in milk- this book reflects growing posthumanist and ecological cultural interest in multispecies interaction and understanding. But to finish, we go back to 1947 for abstract artist and poet Charles G. Shaw’s picturebook It Looked Like Spilt Milk. This book simply explores a number of things spilt milk can look like. There is no judgement about who spilt the milk, just dreamy speculation and observation. The book acts like many of Shaw’s artworks: playful, open-ended and non-didactic. It is a testament to children’s unadulterated imagination -their own, free imagination- being the most powerful food of all.