Christina Macrae

In the run up to our first workshop, focussed on movement, I took an opportunity explore some of the legacies that lie behind the motor developmental stages that the Red Book outlines.

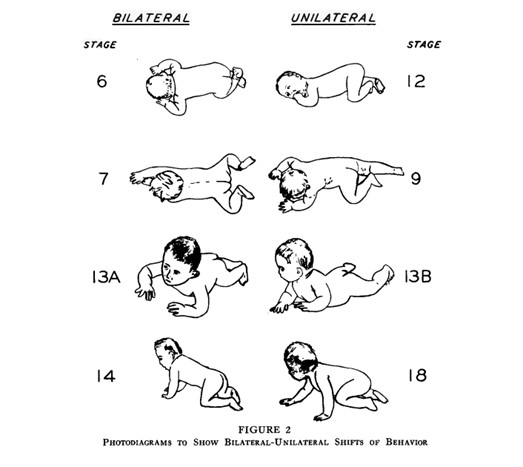

In the past I have been struck by the outline drawings of babies and toddlers that I associate with books, leaflets and pamphlets for parents (as well as for professional training in child development). They had reminded me of my NHS Red Book that accompanied my babies, given to me by my midwives. As part of a previous project, I had started to explore some of the histories behind these depictions of the motor development of babies and toddlers as I had noticed how they carry pre-echoes of those in the Red Book. I had been interested in how these “graphic figurations of the growing infant continue to haunt paediatrics, and their depictions of ‘indices of normal development’ (Curtis, 2011:423)“( MacRae, 2019). I first identified these graphic figures in a book by Gesell and Ames in 1940.

For want of a better way to describe them, I called these outlines of babies abstracted from time and their milieu “bubble-body-babies”. These drawings were produced through Gesell’s experimental method of 360-degree filming infants inside a one-way visual screen. This device “The Gesell Observation Dome” aimed to (re)create naturalistic conditions at the centre – from which he was able to harness the objective verity of film as the method by which to assist “science to make the intangible tangible” (Curtis, 2011:418).

Gesell then rendered film into separate frames to create progressive sequences of motor-action used to demonstrate his maturational theory of development. From these mass archives of photographic sequences were collected and large two volumes Atlas of Children’s Growth produced. He then finally began the project of extracting (or “in his words “dissecting”) the outlines of the infant body, using a machine he invented called an “analytic projector”. This machine projected frames onto paper and then rendered children’s bodies as line drawings (Gesell, 1946). These selected images had the effect of simplifying the stages of growth that he had elaborated in such depth and detail. Thus he presented the sequential development of key motor events. Goldfield talks about Gesell’s “air theory” legacy, as these drawings have the effect of suspending infants “in a vacuum” (1993:52).

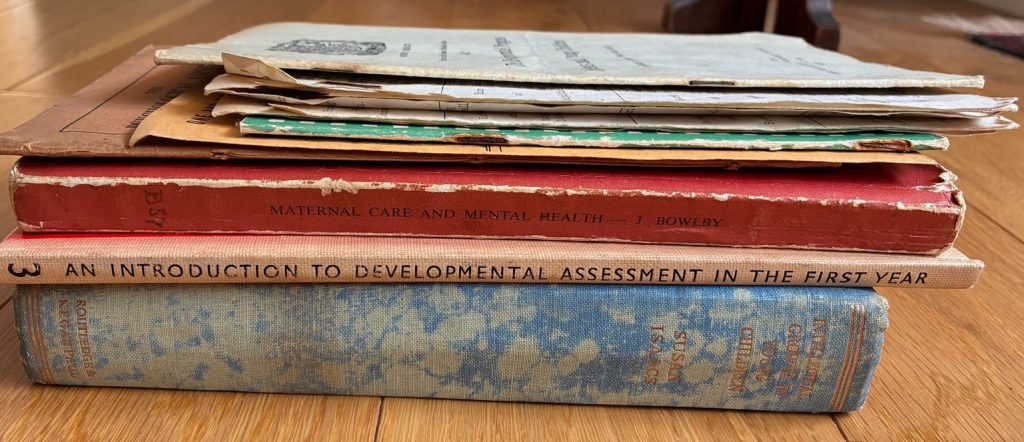

I then also noticed very similar depictions in the charts and books by Mary Sheridan, that have dominated post-war paediatrics in the UK. I have a personal interest in this as I had inherited a collection of child development guides from my grandmother, who after the war, was working in woman’s health and paediatrics. Many of these (carrying my grandmother’s annotated notes to assist her in task making developmental assessments of children) were by Sheridan.

When preparing for this workshop, I was surprised to discover that Mary Sheridan’s influence on child development theory in the UK is much more pervasive and recent than the well-worn post-war pamphlets handed down by my grandmother. Her book “From Birth to Five Years” was first published in 1973, and has gone through 5 editions since then, latest coming out in 2022. A little more research told me how much Sheridan was influenced by Gesell’s work. In turn, Gesell, is very much the disciple of Stanley Hall, the self-proclaimed father of evolutionary child study, and recapitulation theorist. As Knight has noted, “the relationship between emerging theories of child development and Man is perhaps most evident in recapitulation theory” and this “construction of development through childhood” (2024:9)

Back in 1885, writing in The Youth’s Companion, Hall implores “every mother, aunt, teacher, or father” to keep a “book about the baby” (1895, p. 106). He goes on to say he hope is that this book

“might be opened the day the child was born. In it should be noted anything whatever about the child’s development: the first time it uses each new word, its progress in sitting erect, holding up the head, standing and walking; its favorite toys and plays, all salient little speeches, mistakes, questions; all the observer’s efforts, fears, successes, etc. How invaluable such a “life book” would be if well kept…” (Hall, 1895, p. 106)

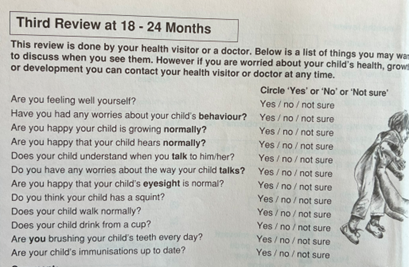

This feels to me like a kind of fore-shadowing of the Red Book, albeit that in its current iteration, the Red Book sits uneasily as a document for health professionals to monitor a child’s health and identify ‘atypical’ patterns of physical development, whilst at the same time it invites parents’ observations and attempts to make space for more personal family mementoes of the ‘first’ milestones of development (eg words and steps).

While many research articles talk about how Gesell’s theories have been super-ceded, and carry little weight, it started to feel as if these graphic figurations of the growing infant, do carry considerable influence and impact as they underpin (and haunt) the frontline practices of midwives, early years practitioners, and associated health professionals in the UK to this day. I am struck how the Red Book carries some strong threads of connection that can be traced back to Hall, via Gesell. In its linear and progressive mapping of development, I see traces of Hall and Gesell’s ambitions to encapsulate child development theory within a grand evolutionary theory of human history. In the graphic figures of the “bubble-body-babies”, I see hauntings of the stages of growth mapped by Gesell’s method of photo analysis. This is a reminds me how Gesell expanded Hall’s Mass observation project with photography as a way of establishing a scientific truth in relation to child development, and the insinuation of

“a scientific method of comparison and correlation, where theory and method are “mutually reinforcing” (Curtis: 428/9). Normalcy is constructed …whereby each frame marks out and stands in for a moment in progressive time – each moment as bounded one in the inexorable passage of evolutionary time” (MacRae, 2019)

Donna Varga points out this is a particular form of “colonization of childhood through developmental science” that is applied through “a belief system characterised by a desire to know everything about children to improve their lives” (2011:138). She further notes that this has the effect of only considering features that are valued by those whose theories and methods are constructing a particular version of the child: a white normality. And this sense of establishing and identifying normalcy comes right through and in bold letters in the Red Book. This type-casting project, while ostensibly mapping the ‘typical’, by its logic is continually producing the untypical: the abnormal, What was identified by Gesell as ‘retarded’, then later by Sheridan as ‘sub-normal’, is now designated ‘atypical’ or ‘developmental delay’ in today’s Red Book.

Just as I am completing this blog entry, Wes Streeting, health minister for the Labour Party announces with fanfare that the Red Book will be taken online – so its future is now as a virtual ‘book’. In social media, I see mixed responses to this from parents, some dismayed that this tangible record and memento of their child is being phased out. I also am aware how these virtual Red Books are already being trialled, with parents who are increasingly being expected to undertake the 18 month and 24 month checks themselves. To support them to ensure their child reaches the age expected stages, they come with instructional videos of activities to do with their child in order that they hit their milestones when they ‘typically’ should.

In our Toddlerhood workshop, when I presented these histories that haunt the Red Book many participants shared what were sometimes quite visceral memories of anxiety and guilt that they associated with the Red Book. The resulting discussions we had in the workshop provoked us to ask more questions:

- How do the developmental narratives of toddlerhood affect us as adults? how do they affect our relationships with toddlers?

- What do ‘Developmental progress’ accounts of children’s ‘physical development’ do to us as adult human bodies? And what do they do to toddler bodies?

- What do we lose and what do we gain when certain milestones of development become markers that celebrate a child’s success ?

References

Curtis, S., (2011) “Tangible as Tissue”: Arnold Gesell, Infant Behavior, and Film Analysis, Science in Context, 24:3, 417–442

Gesell, A. (1935). “Cinemanalysis: A Method of Behavior Study.” Journal of Genetic Psychology 47(1):3–16.

Gesell, A (1946) “Cinematography and the Study of Child Development,” The American Naturalist, 80

Goldfield, E (1993) “Dynamic Systems in Development Action Systems” in A Dynamic Systems approach to Development of Cognition and Action, eds. Smith, L.B. and Thelen, E. MIT Press: London

Knight, H. (2024). Histories of childhood and man: Implications for childhood studies. Childhood, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/09075682241306839

MacRae, C. (2019). ‘Grace Taking Form’, Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 4(1), 151-166. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/23644583-00401003

Sheridan, M. (2022) “From Birth to Five Years” Varga, D. (2011) LOOK – NORMAL: The Colonized Child of Developmental Science, History of Psychology, (14:2), 137–157

Young, J. L. (2016). G. Stanley Hall, Child Study, and the American Public. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 177(6), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2016.1240000